13

Foreign Relations

It’s more than somewhat disconcerting to find, when you’ve sorted things out in your own mind and determined on a clear course of action, that other people haven’t been waiting around for you to get off your chuff. Not that Hill had expected Hattie would, on her form up to now, but…

“I suppose Germany is marginally preferable to Japan,” he said grimly to the phone.

“Mm. I’m sorry, Hill,” replied Joanna glumly. “It’s the same lot. I mean, the Germans that had the meeting in Japan.”

“When will she be back, Joanna?” he asked heavily.

The answer was a lemon: about another week. By that time they’d be nearly in May, for God’s sake! Grimly he thanked her and hung up. Shit! Grimly he pressed the intercom button and asked Hellen for a coffee.

She came in with it looking her usual serene self and reminded him calmly that it was almost lunchtime and he had that meeting with his solicitor, and after that Sir Maurice would like to see him.

“Chipping Abbas?” he said grimly. “Or more potty ecolodges?”

“More on that theme,” replied his perfect secretary. She laid three folders on his desk.

Aw, gee. The folder labelled “Ecolodges: Preliminary Feasibility Studies” was simply coded dark brown but the other two, “Fern Gully Ecolodge Feasibility Study” and “Big Rock Bay Ecolodge Project Plan,” were coded respectively dark brown with dark green and dark brown with yellow. Hill didn’t say anything at all about the dangers of over-elaboration in any sort of coding because he was perfectly well aware that Hellen was perfectly well aware of that and that it was a joke. What he did say was, very grimly: “You can bloody well take the minutes.”

“Certainly,” Hellen replied calmly, going out.

Hill drank coffee grimly.

Half an hour later he looked numbly at old Partridge. “What? Why?”

The lawyers had finally tracked down Col Tarlington’s first wife and daughter but the latter, though she was living in Britain, had refused absolutely to have any sort of contact with Sir Hilliard and he was afraid he couldn’t give him her address.

“Er—all she said was that she didn’t wish to have anything to do with any Tarlington, Sir Hilliard. I’m afraid the mother’s divorce still—er—rankles.”

“Right. Is the mother in Britain, too?”

“No.”

“And she isn’t in want?”

“Well, no, Sir Hilliard, far from being in want I gather she’s since remarried and divorced twice and, er, found another, er, partner.”

“Protector, I think you mean. So much the better. Well, uh, Pa did once say something about her being that type, but given Col’s reputation we assumed the fault was on his side.”

“I rather think it was, initially, Sir Hilliard,” he murmured.

“Do you remember her, Mr Partridge?” asked Hill curiously.

“Well, yes. A very attractive young woman, with a great mass of blonde curls. Long hair was very popular with the younger set, back in the Seventies, of course.”

Er—yeah. Partridge himself must have been young back then: he was only about sixty now, though he came on like Methuselah’s uncle.

“Mm; I get the picture. Well, if the daughter doesn’t want to see me, she doesn’t. But—uh—I feel she should have something from her father’s estate.”

Politely Mr Partridge reminded him that Chipping Abbas and its contents were entailed. Quite. Hill thanked him for his efforts and went off to grab some lunch, frowning.

The afternoon’s meeting about the ecolodges went quite well, though Maurice was still very annoyed that they hadn’t managed to head-hunt the architect he wanted. He’d decided to concentrate on the Queensland ecolodge for the time being and invite several architects to put forward concepts for the other one. So be it—Hill didn’t give a stuff who designed it or what it looked like, frankly. Maurice then decided that Hill could get out to Australia next month and make sure the chap that Thompson had appointed to oversee the work on site knew what he was doing, but in the meantime they’d better have a project planning and consolidation meeting about Chipping Abbas.

Oh, God. But Hill didn’t bother to point out that the Chipping Abbas project was going along perfectly well, he knew by now that that was how YDI operated. You didn’t just think it out, make a decision and do it, you had to talk about it. As far as he could see the rest of the project management world was the same, so he wouldn’t have been any better off anywhere else, so there wasn’t much point in moaning about it, was there?

Maurice cleared his throat. “Er, thing is, the people from the Gano Group would like to see things for themselves. Very interested in my idea for making Chipping Abbas a centre for hospitality excellence.”

“That’s good,” said Hill with patent insincerity.

Maurice smiled nicely. “Thought you could show ’em round, old man.”

Hill took a deep breath, managed not to tell his boss to eat his shorts, and agreed he would do that.

He was pretty well used to getting up at crack of dawn, but Japanese businessmen and their entourages, he had discovered during his employment at YDI, got up considerably before crack of dawn. Possibly they had that adage about early birds and worms in Japanese, too? They even got up before crack of dawn after Goddawful dinners with Maurice Bishop and the second wife, who was just as frightfully snobbish, not to say parochial and xenophobic, as the first one had been, so why on earth he’d bothered with the divorce— Added to which, she didn’t even give the impression of being a woman who enjoyed sex! Hill did have some respect for old Maurice as a businessman but, alas, getting to know Lady Bishop had measurably diminished his respect for him as a man. Maybe the Japs had the right idea, never taking their business chums home to meet the wife. Because God knew, if the helpmeet was a disaster you couldn’t help tempering your opinion of the chap, could you?

He duly crawled out of bed, and crawled off to meet Mr Watanabe and his cohorts at their hotel. It wasn’t one of YDI’s, they didn’t own any city hotels, so at least they couldn’t be blamed for the fact that it offered a choice of English or Continental breakfast.—Wogs started at Calais, and Abroad ended at Monte: quite.—Mr Watanabe and Co. were politely eating toast without butter and drinking coffee without milk in a very empty dining-room. There was a buffet instead of table service but presumably the presence of the coffee and toast indicated they’d grasped what to do. Greetings were exchanged—Watanabe’s English was reasonable, so was that of the two younger chaps with him, but the two older guys didn’t speak much—and, Hill having sat down and politely agreed to a coffee, the youngest assistant got up to get it for him and bowed deeply, making a short speech in Japanese. Watanabe returned a brief reply and then the young chap bowed to Hill and said: “Would you rike some fuh-ruit, sir?”

Hill had already said he’d had breakfast. “Fruit? Uh—no, thanks. I’ve had breakfast.”

“Ah. So sor-ree.” Bowing frightfully, the young chap hurried off to the buffet.

“He rikes fuh-ruit,” said Watanabe carefully. “I have said that he may serrect some.”

Jesus, was this gonna go on all day? “Good show,” said Hill with an effort. Toshiro Watanabe was an Executive Director, and son of old Watanabe, the Chairman of the Board and a very major stockholder in both the Gano Group and YDI. Well, in all of the Group’s subsidiaries. He never travelled. And rarely invited anyone to come to him, especially not foreigners. Was all the kow-towing because Toshiro was the son and heir, or did the man expect it? He had struck Hill yesterday as quite a reasonable chap. Actually his English hadn’t struck him as quite that bad: maybe it needed lubricating by Maurice’s single malt and Maurice’s burgundy in order to flow smoothly. Damn.

The two older men were conferring in lowered voices. The one with a broad, toad-like face was looking very sour but perhaps that was his customary expression. He’d certainly looked pretty sour over the traditional English roast beef that Lady Bishop had offered last night but possibly that was because the Japanese idea of beef was something corn-fed that a butter knife could slip through. Hill had found the roast excellent, but why should the whole world be expected to enjoy a mixture of singed, crusty outside and bloody, dripping inside? The thinner man, the one with a rather hawk-like face, finally said something to Watanabe, as the young assistant came back to the table with Hill’s coffee and half a pink grapefruit for himself.

“Hai,” agreed Watanabe. “Mr Tar-ring-uh-ton, we rook forward greater-lee to see Chipping-ah Abbas. Mr Takagaki is most interest’ in-ah hotel-luhs.”

“Most interest’,” agreed the hawk-faced Takagaki.

“Good,” said Hill feebly, smiling at him.

“Howevah,” pursued Watanabe, “he wishes to ask many questions. Is it possible to have interpret-ah for him?”

Ouch! Why hadn’t the idiots said at the outset they’d need an interpreter? “I’ll see what can be done. Excuse me.” He outed with the mobile phone and rang Hellen.

“They’re leaving now, are they?” she said drily.

“In a few minutes, yes.”

“Well, I’m sorry, but it’s beyond my merely mortal powers to magic you up an interpreter to go down with you.”

“Thought so, mm.”

“Sitting there drinking in your every word, are they?” said Hellen with a laugh in her voice.

“Possibly not the drinking part, but yes.”

“Most of them understand more than they speak. Comes of spending hours in front of the telly watching the Yank shows.”

“Yes. I trust that persiflage is veiling the fact that you’re thinking?”

“Mm. I’ll ring the hotel. Got a few spies in Ditterminster, too: they may be able to help.”

“Okay: thanks, Hellen. Ring me back as soon as you know anything.” He rang off and told them his secretary was looking for an interpreter for them. Profuse thanks followed as night the day. Profuse and very premature.

Possibly part of his task for the morning might have been to ride with them and answer, or perhaps parry was a better word, anything they asked about the Chipping Abbas Conversion Project, but as he had his Range Rover in town he made that an excuse not to go in the limo with them. He made sure the limo driver had grasped that they were headed for the Boddiford Hall Park Royal and off they went, in procession.

Hellen rang back when he was more than halfway there and starting to quietly panic. “The Boddiford Hall types were very cross: seemed to take it as a direct criticism of their ability to lay on a full translation service. Which they can do, with proper notice,” she noted drily.

“All right, Hellen, just give me the bad news!”

“It isn’t all bad. This afternoon’s out, but there’s an interpreter you can have this evening and all weekend if necessary. Seems to be the local mayor’s pet interpreter—well, I didn’t listen to all the details, just made sure your project management terms weren’t going to be a problem. They won’t be: the city council’s involved in some frightful development project with a Japanese consortium and this interpreter’s been doing what the mayoral aide described as three-way translating. More than competent, I gather.”

“Good show. Sure this afternoon’s out?”

“I’m afraid so.”

He sighed but said: “Okay, we’ll have to settle for this evening, then. And grovelling thanks, Hellen, you’re a miracle worker!”

“I saw a very nice bangle in Bond Street last week,” replied Hellen detachedly.

“Uh, not Bond Street, much though I love you. Bunch of flahs?”

“I’ll settle for that!” said Hellen with a laugh. “Take care!”

Unfortunately getting up before crack of dawn to drive over to Wiltshire meant that it wasn’t nearly lunchtime when one got there. Hill saw Watanabe safely installed in his suite and desperately suggested they might like traditional English elevenses. The toad and the hawk merely looked blank but the two young fellows, looking very puzzled, consulted their watches, muttered together and then bowed to Watanabe and muttered something. Watanabe said very politely that a cup of tea would be very welcome-ah—possibly that had been in the phrasebook from which, Hill had now decided, he had learned his English.

“Shall we just have a cup of tea here in the suite, then?” he suggested feebly.

“That would be derightfu’,” replied Watanabe, bowing slightly.

Oops: Room Service, even though he noted pointedly he was ringing from Mr Watanabe’s suite, couldn’t offer Japanese green tea. Once Hill had revealed who he was Room Service, gulping slightly, admitted that his boss was Harry, but he wasn’t on shift at the moment but, um, would he like to speak to the assistant under-manager?

Hill was about to say he’d speak to the Manager, thanks, when a soft voice said: “Hullo, Hill, it’s Joanna Broadbent speaking. Can I help you?”

“Hullo, Joanna,” he said feebly. “I’m in Mr Watanabe’s suite. We were just ordering tea and I thought it might be nice if there was some Japanese green tea, but they don’t seem to have it.”

“No, I’m afraid not. There is some green tea, but it’s Chinese: green leaves.”

“That sounds okay.”

“No, Hattie says Japanese green tea is different. There is a nice little Japanese shop in Ditterminster, so I’ve sent someone over there for some proper green tea. Hattie says it’s like a powder. They whisk it up with, um, little whisks,” said Joanna somewhat weakly.

Er—right. Got it. He settled for ordinary tea and since Watanabe replied with a bow: “Prease—you choose-ah,” to his polite deferral to him, settled for Twining’s Queen Mary for six, on the assumption they’d have to really try, to ruin that.

“Thank you. That was derightfu’,” said Watanabe as he set down his empty cup. Yep, he’d definitely learned his English from a phrasebook.

“Thank you. That was derightfu’,” chorused the others thankfully. Except the toad: he just grunted something in Japanese.

“Mr Mitsubishi alluh-so says thank you for the derightfu’ tea,” explained the youngest aide, perhaps perked up by the tannin.

“Not at all,” said Hill feebly, wishing he could stop twitching every time the toad’s name was mentioned: he did know it was a common name in Japan. And you wouldn’t twitch if an English chap was called Austin or Morris, would you? “I’m glad you all enjoyed it.”

And with that it was ho! for Chipping Abbas. Or put it like this: he wouldn’t have spent another five minutes in the bloody suite to save his soul.

The limo had gone back to London. Shit! Who the Hell had arranged this jaunt? Not Hellen, of course. Maurice’s bloody PA? There being no point in recriminations, he packed them all into the Range Rover, Watanabe in front with him, and he didn’t care how or if the others fitted themselves in.

“The guests at the Boddiford Hall Park Royal,” he said grimly on the firm’s behalf, “usually bring their own cars.”

“Ah,” replied Watanabe.

“The hotel has a couple of minibuses, but they’re busy taking parties of guests on tours.”

“Ah.”

“What can see on tours?” asked one of the young chaps from the back.

“There’s a choice. Either Chipping Ditter village—we’ll be there in a few minutes—or Daynesford Place. That’s a stately home. Um, historic building?” he offered into the dubious silence. “Uh, big country house,” he said feebly. “A mansion.”

“Ah. Thank you, Mr Tar-ring-ton-ah.” –Had he got it?

Well, somebody had. “Engerish stater-ree home-uh!” said the other young fellow excitedly. “We have-ah seen-ah Woburn-ah Abbey,” he explained laboriously.

“Jolly good. Daynesford Place is rather like that.” Architecturally it was a younger brother to Blenheim Palace but he wasn’t up for explaining that.

“Just visit?” asked Watanabe abruptly.

Did he imagine that YDI’d be stupid enough to convert a third country house within an hour’s drive of something nigh the size of Blenheim that was already offering— “Yes, one just visits. They don’t have any catering facilities apart from a small kiosk—er, a small shop that sells soft-drinks and ices.”

“Ah.”

“It is a very beautiful mansion, sir,” said Hill desperately.

“Ah—yes.” He paused. “Balloca,” he said.

Balloca to you, too! “I’m sorry, I didn’t get that,” said Hill feebly.

“Bal-lo-cah,” he repeated carefully.

Right: with brass knobs on! Bal-lo-cah… Oh, good grief! Couldn’t he please just die now? “Yes, it is Baroque,” he said feebly.

Something excited came from the back seat, some words of which might have been English, but Hill was past trying to translate it; he just said very firmly and cheerfully: “I’m glad you like the Baroque. So do I: I’ll put some Baroque music on,” and shoved a Bach tape in the player.

They drove through the narrow streets of Chipping Ditter with their almost completely restored cobbles, fake gas lamps, sparkling whitewash, unlikely window-boxes, ancient brick, half-timbering, very new thatch, et al. to the accompaniment of the Brandenburgs, more than loud enough to make it very easy to pretend he didn’t perceive there was a running commentary from the back seat. Watanabe also ignored it, whether because he didn’t care, didn’t like horribly dinkified old-ee English-ee villages, or actually liked Bach and was trying to listen to it, Hill was past caring.

Funnily enough no galloping progress had been made at Chipping Abbas. Down below the west terrace some of Red Watkins’s merry men were mucking about with bulldozers, diggers and graders in a sea of mud. Off to the side of it was a lone landscape designer in his wellies, holding a giant plan and frowning.

“Hullo, Warwick,” said Hill on a weak note. He had nothing against the man, but his name was Warwick Reston, and what were the Japanese tongues gonna make of that? He duly presented him. Old Mitsubishi just grunted, but the others tried out their English. The results could only be described as ’orrible.

“You might like to see the plan. This will be the formal rose garden,” said Hill slowly and carefully to Watanabe.

Obligingly Warwick showed them the plan, explaining gratuitously and very evidently incomprehensibly that this was the site of the old formal rose garden and the plan was an adaptation of a genuine early one found in the estate office— Etcetera.

“Ah. Lohses. Berry pretty,” said one of the young aides at last.

Old Mitsubishi suddenly burst into speech. The unfortunate young chap bowed and stuttered out something in reply. The old man growled out something short and pretty sharp—though that might mean nothing, he was very like the heavies in Japanese costume films. Or, come to think of it, Japanese gangster films.

Bowing desperately and smiling very nicely, the young man said to Hill: “Mr Mitsubishi would-ah rike to know, will there be-ah… fence?”

“A fence? Um, no, it’ll all be, um, open-plan,” said Hill on a weak note. “Um, can you explain, Warwick?” he added weakly.

Mitsubishi had now grabbed the plan so Warwick was able to wave both arms as he explained. He was quite a young man, and very keen on his subject, so there was perhaps some excuse for his not having grasped that what was needed was not an explanation but a clear statement in very plain English.

“Ah… Yes. Thank you berry much, sir,” said the young aide. Mitsubishi grunted out something and, bowing desperately, the young fellow burst into speech. Judging by the reception he got, he hadn’t grasped a word Warwick had said. Either that or the old chap didn’t like open-plan formal rose gardens dating in inspiration back to around Aden Tarlington’s time. Or a little earlier: Warwick had consulted some beautifully illustrated volumes on rose varieties which had come out in the late 18th century. In French, strangely enough: an incongruous preoccupation, whilst they were simultaneously chopping off their rulers’ heads.

“Mr Mitsubishi is berry interest’ in-ah lohses,” said the young man. “He would-ah rike to know, will there be-ah… fence? Ah… fence for lohses,” he elaborated.

Hill just looked wildly at Warwick, but he said: “Oh! I see what he means, Hill! –You mean a trellis. For the roses to climb on,” he said kindly to the young Japanese. “Not here, there won’t: this is a formal garden in the style of the late 18th century, but we’re restoring the trellises back on the terraces.”

It wasn’t gonna get better, was it? “Please tell Mr Mitsubishi,” said Hill, smiling very nicely at both the old man and the young one, “that there will be fences for the roses against the walls of the house.”

“Ah! Thank you, sir!” Excitedly he conveyed this information. Mitsubishi grunted, but made a short speech that didn’t sound too displeased. Unfortunately its visible effect was to reduce the young chap almost to tears.

Before he could speak, however, Watanabe made a short and pithy statement. To Hill’s horror old Mitsubishi then bowed to him and muttered something that sounded ’orribly ’umble. Hell’s teeth, had it been a reproof?

Watanabe then said: “Mr Mitsubishi would-ah rike to know names of lohses. I have said, not-ah possibuh.”

How true. However, Hill tried to indicate there were more detailed plans back at the house. He led them off. The younger ones were smiling like anything. Takagaki also looked pleased. Mitsubishi looked toad-like and Watanabe looked completely inscrutable, so there you were.

Well, there they certainly all were in the library standing looking at Warwick’s beautifully detailed plans for the rose beds. After some time Hill got them to go out onto the east terrace and he and Warwick just sagged.

Finally the young landscape designer offered feebly: “I think they were pleased that I took my boots off to come into the house.”

Possibly—yes. Not that he’d have done much harm: most of the floors were shrouded in heavy canvas. “All things are possible, Warwick,” Hill replied heavily.

“How long have you had them?” murmured Warwick.

He took a deep breath. “Since before the dawn of time.”

Naturally it didn’t get better. Takagaki managed to ask where the pictures from the long gallery upstairs had gone. (Point at empty walls, “Where pick-ah-tooh-ah?”) Watanabe managed to point out that the ballroom and the suite above the west terrace were “Not-ah light-ah period.”

“No,” agreed Hill without hope. “We are trying to preserve some of the history of the house.”

“History,” he echoed. “Ah. Yes. History.”

Takagaki was very keen to see the kitchens but very disappointed when they got there. Well, Hell, they had only just started, and obviously Step One had been to rip everything out.

“Not—finished,” said Hill slowly and carefully.

“Yes. Ah… all-ah new?”

Did this mean— Forget it. Hill replied cheerfully: “Yes,” and this seemed to satisfy him.

Watanabe then wanted to see the house from “all a-lound-ah,” his English was definitely getting worse—not that Hill blamed him for this, poor chap, after all he himself knew three words of Japanese: but why the Hell hadn’t they admitted in the first place they’d need an interpreter?—and so they went outside and did that.

“I would rike-ah see all-ah puh-lan,” he then said carefully.

In that case they’d be here till Christmas! Resignedly Hill led them off to the estate office, which he was using as the project office. Gee, it was not-ah light-ah period, fancy that!

He got out the huge volumes which held all the plans and laid them on the desk, nay, piled them on the desk in front of him.

“Thank you. Prease show puh-lan of period of all ur-room’ for guests.”

It was at about this point that Hill gave up entirely on the careful-English-to-foreigners shit: the man had had the brass face to ask for it, so he could bloody well have it! “The styles are indicated on the artists’ impressions of each room or suite. There is no one plan which shows them all. It’s this volume.” He opened it for him and stood back.

Watanabe looked through it very slowly. Everyone else stood around like spare parts. There was only one guest chair in the office and as Hill wasn’t sure of the pecking order he didn’t dare to offer it to either Mitsubishi or Takagaki, so it just stood there, too. Finally Watanabe looked up and said: “Where puh-lan for this ur-room?”

“This isn’t a public room,“ replied Hill flatly.

There was a moment’s silence. “This is old-ah office?”

“Yes, the old estate office.”

Watanabe spoke at length to his staff. Takagaki seemed to be agreeing with him. Mitsubishi grunted out something that could have meant anything. Then Watanabe addressed a speech to the older of the two aides, oh, no!

The poor young fellow took a deep breath and said: “Mr Tar-ring-ton-ah, Mr Watanabe thinks guests be very interest’ in old-ah office. All-ah part of old-ah house very interest’.”

Watanabe burst into speech again. “Hai!” said the young man, bowing. “Alluh-so,” he said to Hill with a frantic gleam in his eye, “old house for-ah horr-uh-suh.”

Horror-suh? He’d lost Hill, there. Hang on… Hor-uh-suh. Hor-suh? “Horses?” he croaked. “The stables?”

“Ah! Yes! Thank you berry much! Stay-buh—”

“Yeah. Don’t bother,” said Hill heavily. “I see. At the moment I need this room as an office. We’ll think about refurbishing it later. It’s time for lunch: come along, we’ll go back to the hotel. You can see the stables this afternoon, if you like.” He went over to the door and held it wide. Either they were as hungry and desperate as he was, or they were too well-mannered to object— Whatever, they filed out obediently.

The journey back to the Boddiford Hall Park Royal was accompanied by more Bach and what sounded like a confab between the two older execs in the back but Hill was past caring what it was about. Way, way past. Watanabe didn’t utter, so perhaps he’d had it, too.

They went to their rooms before lunch so he seized the chance to have a word with Joanna. The green tea had been procured. Um, no, she didn’t think she could see to it that the lunch service was slow, Hill, because they didn’t want them to get a bad impression of the hotel!

“No, of course not: sorry. I was forgetting that they’ve got all your jobs in their hands, as well.”

“Mm. I bet a memo’s already gone to Tokyo about the tea,” she said glumly.

It was hard to remember back that far but he didn’t think they’d had the opportunity. More likely it was winging its way across cyberspace as of this very moment, along with the memos about the not-right periods at Chipping Abbas and the lack of a consolidated period plan and the sea of mud in the grounds and the absence of interpreters in the middle of rural Wiltshire and— Yeah. Like that.

“Is there any sake?” he said heavily.

“Yes, loads. Only the thing is, we don’t do Japanese meals, so they may not order—”

“No. What is on for lunch?”

She had a menu here for him. For an assistant under-manager in the middle of rural Wiltshire she was quite an efficient creature, really, wasn’t she? He read it through rapidly, and sagged. “Lots of fish.”

“It’s Friday,” replied Joanna simply.

Oh, so it was. Felt like Thursday of three weeks hence. “What about the weekend?” he croaked.

“There’ll be plenty of fish again. Chef’s got a couple of lovely turbot for tomorrow’s dinner: really huge ones!”

“Ye-ah. Um, this is for the conference buffet, is it?”

“Yes; they did say they wanted the Gano Group people to see a conference buffet and as we didn’t have an outside one booked in—”

“Yeah. Um, look, Joanna, there’ll be people there who’ve never seen a turbot in their lives—”

“It’s all right, the staff will serve the meal.”

Hill sagged again. “Right: American-type buffet, eh?”

“That’s right,” she said, smiling. “We’ve found that unless they’ve had a lot to drink people like it better if they can be served.”

Hill thought of some of the large buffets he’d been to in his time and winced. “See what you mean. If they’re grogged-up they grab and stuff themselves regardless, but if they’re not, they hang back and the food goes to waste.”

“And Chef tears his hair; yes!” she said with a giggle.

“Mm. Talking of drunken behaviour at buffets, got any wedding receptions booked in this weekend?”

“Well, yes,” said Joanna in some surprise. “It’s too chilly for them to book The Grove for the actual ceremony, of course, but The Huntsman’s Repose is booked for a wedding lunch tomorrow, and another party’s booked the Solarium for tomorrow afternoon—it does mean we’ll have to serve the teas in the main lounge, but Saturday’s not usually as popular as Sunday for the tea crowd.”

“That sounds promising! Japanese like weddings, don’t they?” said Hill happily. “Well, I mean, lots of them travel halfway round the world to get married in our quaint western ch—” The look on her face registered. “And?”

“Some very doggy people have booked the ballroom for a wedding reception this afternoon.”

The hotel did specialise in catering for pampered pooches, but… “How doggy, Joanna?”

“The thing is, we booked them in before we knew the Gano Group people would be coming this weekend. It’s the man who runs the local pack of hounds—not fox hunting, don’t worry, there won’t be any protesters! They drag a scent thing. It’s his daughter’s wedding.”

“Joanna, just state plainly whether the place is going to be overrun by a pack of yelping hounds while I’ve got the Japs on my hands!” said Hill loudly.

She swallowed. “Yes. Well, later in the afternoon. They’re supposed to, um, mill around on the sweep”—Hill closed his eyes—“for the last lot of photos: you know, when the bride and groom leave.”

“Clattering tin cans tied to the back of a car in the middle of a pack of foxhounds?” he croaked.

“They did say they wouldn’t,” she said weakly.

“Right, them and all the younger brothers and old school chums of the groom’s!”

“Maybe you’d better keep the Japanese over at Chipping Abbas,” she said weakly.

“We can’t talk, and if they’ve seen everything how the Hell am I supposed to do that?” he demanded wildly.

“I dunno,” said Joanna wanly.

Hill bit his lip. “No. Sorry. Not your problem.”

“Um, give them tea in the village?”

“Well, yeah, good idea; I’ll try it. Trouble is, they don’t seem as keen on stuffing their faces as the Occidental side. Oh, well; plug on.”

“Mm. And Chef’s fish’ll be lovely,” she assured him anxiously.

There was no doubt of that. He nodded, thanked her for managing the green tea, and trudged off to get on with it.

The fish was lovely, and the Japanese seemed to enjoy it, but they didn’t order any wine, so there was no hope they’d pass out for the rest of the afternoon, or not care what they saw for the rest of the afternoon, or stop asking questions in incomprehensible English for the rest of the— Yeah. Hill didn’t think they were merely following his example, he thought they were just naturally the sort that didn’t drink at lunchtime. He certainly didn’t order any wine: for one thing, he’d have to drive this afternoon; for another thing, he was supposed to be bloody working, not that that was gonna happen unless some self-sacrificing hero arrived to take them off his hands; and for a third thing, he had a sneaking suspicion that if he consumed any alcohol at all he’d let them see how he really felt about the tremendous waste of time this day had become.

“What would you like to do this afternoon, Mr Watanabe?” he asked politely.

“We would rike to see you work on Chipping-ah Abbas-ah project, prease.”

“It won’t be very exciting for you, I’m afraid.”

“Ah.” They conferred together and the older aide was deputed to give the reply. “Not want excite-ah, thank you berry much, Mr Tar-ring-uh-ton. See work, prease.”

They drove over to Chipping Abbas to the accompaniment of some Telemann. Watanabe was very interested and asked to see the CD, so perhaps he really did like the Balloca.

The older aide reported with some difficulty that Mr Mitsubishi would like to see the lohse garden again so Hill dumped the pair of them on the shrinking Warwick.

Yes, well. The project was under way—certainly the major decisions had been made, such as the layout of the grounds, the fate of the stable and milking parlour and the siting of the swimming-pool, but the architects were still arguing over the interior. Not to say, arguing with Maurice. As Chipping Abbas was going to be a centre for hospitality excellence, we DON’T WANT ENSUITES THE SIZE OF CUPBOARDS! And DON’T try to cram in that many bedrooms, our clients require SUITES! SUITES! That sort of thing. And never MIND where the Goddamned wiring for their Goddamned Internet connections should go, just GET ON WITH IT! That sort of thing as well.

“Where-ah work-uh-men?”

Repressing a groan, Hill tried to explain to Mr Watanabe that the workmen weren’t in here yet: final decisions were still being made. The workmen were in the grounds and the stables.

“Ah!” said the young aide. “See horror-suh!”

“Yes,” said Hill. “Please come this way. The stables are just over here.”

At the stables it was ascertained that there would be horror-suh here, that man use puh-lan (Red Watkins in person: Hill refrained from explaining he was the foreman), and that there was berry much what call-ah this-ah stone-uh. None of them could pronounce the word “marble”, but just to show that, appearances to the contrary, he was on their side, Hill asked the young aide what the Japanese word for horse was and failed to pronounce that. Unfortunately the lad was then emboldened to ask what for litter ur-room-ah. Hill endeavoured by feeble pointing at his own head and neck to indicate what “tack room” meant. But somehow had a feeling that it hadn’t got over. Red came up and explained, grinning: “For saddles. You know, on the horses’ backs.” Gee, it worked. Beaming, the young man managed to say he had heard of their Derby race-uh, see on TV. Red explained it wasn’t on yet, but he knew that. Newbury races’d be the nearest, Red added tolerantly. Watanabe and Takagaki were way down the other end of the block so the young fellow explained sadly: “No can-ah go. Not permit.” Fancy that.

He then went off sadly to join his bosses and Red noted drily: “Next time I get real fed up with baked beans and that bloody rap music young Mal keeps playing in our hut I’ll remind meself of that young shaver.”

“Yeah. Does make you count your blessings,” agreed Hill drily.

“Yeah. –What was all that about per-lans?”

“Eh? Oh: Watanabe. Insisted on seeing all the plans for the house this morning. That went down reasonably well, only now he can’t understand why no-one’s actually got started on the interiors.”

Red winked. “Should of brought Sir Maurice down again, got ’im to do more of that shouting. That’d give ’im an idea or two!”

“Quite.”

Red scratched his chin. “You taken ’em over to the bathhouse yet?”

“No, why?”

“Well, it’s going good, I’m not saying it isn’t, only Jack Barker’s working in there at the moment. And if this big-shot corporate type’s shit-hot on per-lans, ’e won’t like what he sees. Jack Barker’s been working with stone and marble since ’is cradle.”

“Man see puh-lan?” put in a cool Japanese voice, and poor Red jumped ten feet.

“’E’s seen it, yeah,” he admitted. “Last time I looked in on ’im ’e’d stuck it on a ledge with a ruddy great broken piece of marble whojamaflick on top of it.”

“‘Whojamaflick’ is an English idiom, not very common at all, that means ‘something or other’,” said Hill solemnly to the Japanese.

“Thank you, Mr Tar-ring-uh-ton. Ah… man not rook at puh-lan?”

“’E did sort of look at it,” conceded Red glumly.

“The man is a very experienced stonemason, sir,” explained Hill.

“Ah… yes. I see. I would rike-ah see bathhouse-uh, prease.”

“Of course: we can go there, next. It’s not like a Japanese bathhouse, though.”

“I know. I saw puh-lan for bathhouse-uh.”

Right, and he’d understood what he’d seen. Feebly Hill collected up Takagaki and the young fellow and led them over to the former cow palace. In its day, which was the mid-eighteenth century, the dairy complex of Chipping Abbas had been famous. One look at its lovely little marble stalls and the beautiful old drainage roses had decided Julia that it would make a perfect bathhouse—on the lines of the one Hill had had put in at the Cottesford Manor Park Royal! The stalls could be for the special mud treatments! Well, yeah, one treatment table for a spoilt up-market client was about as long as a spoilt Jersey cow with a milkmaid at her nether end. Maurice was thrilled, so chalk one up to Julia.

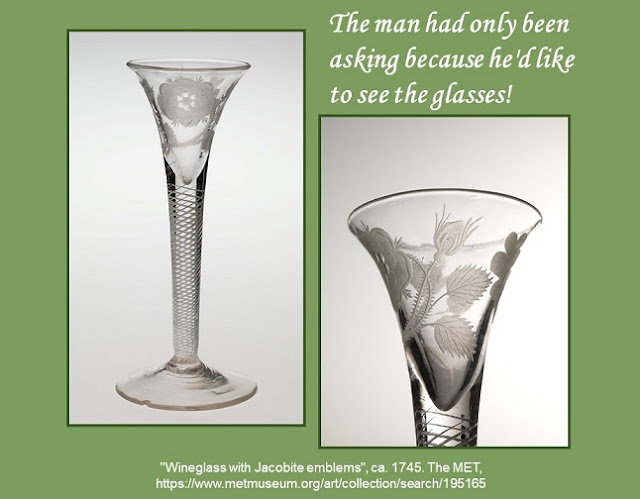

Outside the building two youngish chaps were painting its window frames. They had retained what windows the cow palace had had, including some really lovely cartouche-windows, but were adding a few more to let in a bit more natural light. The etched glass was an inspiration of the interior designer’s: they’d wanted something that would give privacy as well as light.

“Guh-rass not-ah light-ah period,” spotted Watanabe.

“No, though the designs on it are from a set of 18th-century glasses. We wanted something to give the clients privacy.” He looked at him without hope; they had unisex nude public bathing in Japan, didn’t they?

“Ah. Where guh-rasses?”

Carefully packed in a box down at Guillyford Place, actually: no way was bloody Maurice Bishop going to get his hands on them! “Packed away for safe-keeping,” said Hill heavily. “The contents of the house have not all been leased to YDI.”

Quickly the young aide offered what was presumably a translation.

“Keep-ah safe,” agreed Watanabe. “We understand.”

“Hai! Yes. Keep-ah safe,” agreed Takagaki. “Mr Watanabe very interest’. Ah… rike all-ah thing-ah Balloca.”

Oh, shit! The man had only been asking because he’d like to see the glasses! “Of course,” said Hill feebly. “The house is open, as you see, Mr Watanabe, so the contents would not have been safe here. Um, well come inside, sir, the bathhouse is the old cow house, of course, and you’ll see that we’ve kept many of its Baroque features.”

They went in and he showed them its glories. Whether a word sank in he couldn’t have said. Jack Barker was making excellent progress and was only too happy to demonstrate his work, but whether they understood a word of— Never mind. Everyone was putting their best foot forward—nay, visibly putting their best foot forward: that was all that could be hoped for.

In the further course of the afternoon one of the swimming-pool engineers rolled up to the estate office, apparently to tell him something incomprehensible about fill, the craftsman who had been contracted to replace the wrought-iron main gates dropped in to ask if he could see the real designs, and a nurseryman from the far side of Salisbury turned up looking for Warwick with the offer of five thousand genuine old rose varieties. Just when they’d all been sorted out, and Warwick and Mitsubishi, incidentally, discovered down at the back of the old tennis court gloating over the climbing tea roses that had gone wild there, bosom-buddies for life, a thatcher from the far side of Warwickshire turned up with the offer of his services. Completely unsolicited: there was nothing on the property that needed thatching. Hill was about to send him on his way when a Thort struck him, so he rang Mrs Everton. The terrifying parakeet was thrilled, though possibly being rung up by Sir Hilliard in person was a factor— Never mind. He gave the chap her address and sent him on his merry way.

Hellen rang just after that.

“Look, if you’re going to tell me we can’t have that interpreter after all—”

“No, no!” she said with a laugh in her voice. “Just thought I’d better warn you that we’ve had a couple of very strange emails from Tokyo.”

“And?”

“Number one, can we arrange shipping of genuine old English rose varieties. Number two, where can they see genuine 18th-century glass?”

Gee, maybe that was why the young aide had plugged his laptop in. “Jesus!”

“I’m looking into it, but I thought you might like to be forewarned.”

“In this instance I’d have remained happy in my ignorance. But thanks, Hellen. Oh: I’ve got contact details of a thatcher, should we ever need one.”

Hellen took down the details and asked if the man had had references.

“He’s from Warwickshire, isn’t that reference enough?”

His perfect secretary went into a choking fit.

“Yeah,” said Hill with satisfaction. “He did have some references but as I didn’t need him I didn’t make a note of them.”

“We may contact him sooner rather than later, actually: Sir Maurice has found a place in Kent that only needs to be completely gutted, restored and re-thatched to be a perfect exemplar of real Old-ee English-ee hospitality. Though I was under the impression that ‘hospitality’ was a French word in origin,” said Hellen sedately.

“Don’t dare to set me off!” he gasped.

“No, well, be warned, it may be your next project.”

“He didn’t breathe a word of it last night,” he said dubiously.

“In his shoes, I wouldn’t, either: it may never come off. Have you given them tea, yet?”

“Uh—no. Think I should?”

“It’ll break up the day,” she replied simply. “Oh, by the way, there’s a horse and hounds-type wedding at the hotel this after—”

“I know. It’ll be chaos, Hellen.”

“Very Old-ee English-ee, however.”

“Very well, you’ve talked me into it,” he sighed. “That it?”

“For now, yes. Unless we receive any more unlikely emai—”

“Yes! Thank you and goodbye, Hellen!” He hung up. Then he registered the polite Japanese faces. Oh, God. Feebly he conveyed the fact that Hellen was looking after their requests. The thanking and the translating and the more thanking and the bowing made up his mind for him and he led them all off to tea in Chipping Ditter, regardless of whether they wanted it, they thought it appropriate, his stomach wanted it— Regardless.

No comments:

Post a Comment