25

Joanna’s Rescue

Poor Hattie was crying again, and it was gone ten and there was no sign of Hill, and his ruddy phone was off! All right, she’d do it! She wouldn’t tell Hattie, she’d only try to stop her; much better to present her with, um, one of them fate things. French. Anyway, she knew what she meant! Joanna’s mouth firmed. She went and got out of her jeans and tee-shirt and into a good pair of slacks and a nice blouse, she wasn’t gonna let herself down in front of them. But she wasn’t gonna make the mistake of wearing anything too fancy, either, ’cos that’d be wrong, too!

“I’m going for a drive, Hattie, ducks,” she said on a firm note. “I might be quite a while. You’ll be all right, won’t you?”

Hattie had stopped crying and was in the kitchen, mixing flour in a great big bowl. “Of course I’ll be all right,” she said in a grumpy voice.

“What are you making?” asked Joanna nicely.

“Pasta,” she said grimly.

Pasta? It came ready-made, in packets, and if you didn’t fancy that—perfectly all right, nothing wrong with it—the supermarkets over to Ditterminster had the fresh stuff in the more gourmet sections of their fridges! Green and all sorts! And those nice little stuffed packets! Not gnocchi, them other—those other ones.

“They’ll only eat it, you know!” said Joanna with a nervous giggle.

“Good: it might give them some idea that there’s more to pasta than flour, water and salt, like that muck Miriam sells.”

Right. Got it. “Well, see you later,” she said on a weak note, sliding out.

The quickest route was to Ditterminster, straight over to Salisbury, down to Southampton, avoiding London, then the motorway to Portsmouth and after that take the coast road, the one that led to Brighton. Guillyford was just a piece of suburban sprawl, really, with very little of the old village left, and the farm was just on its outskirts. Allan had said that if she ever got lost anyone’d be able to direct her, but that, of course, was before.

Firmly not thinking about before, Joanna drove steadily on, resisting the temptation to go over to London first and drop in on Lorraine or Julian and Bruce. It would be nice to see them but she knew she’d chicken out entirely on bearding Hill in his family home if she did that.

The road to Southampton was pretty clear and she got there much sooner than she’d thought. The short leg over to Portsmouth was quite congested but didn’t take long at all. She wasn’t hungry but she stopped and bought a cup of coffee in a little suburban teashop on the outskirts of the town before heading east.

Heck, she couldn’t remember the turnoff! Um—no… Had she missed it? Um—no… Oh! This was it! She was so relieved that she swung down it and drove through to Guillyford without so much as thinking that she might have to face Allan.

Actually you couldn’t get lost, because as you hit the edge of the shopping area there was this fork and two road signs, that she didn’t remember noticing that other time. One pointed to “Guillyford Village Green” and the other to “Guillyford Place”. Trust them to have a ruddy road sign all to themselves! Joanna drove on, scowling.

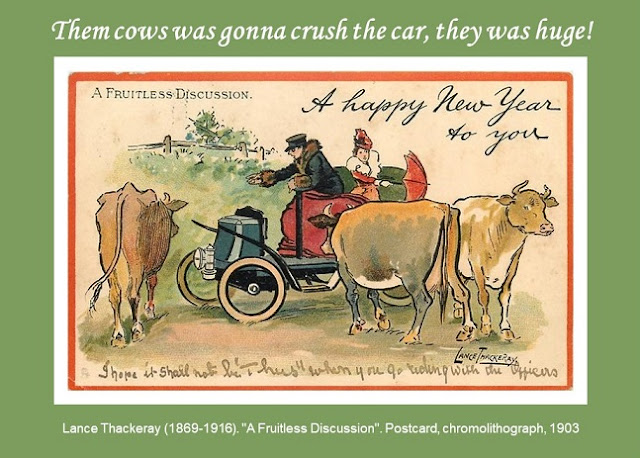

Ooh, help, cows on the road! She braked and slowed to a crawl. Ooh, help, they was all coming up and looking at her and some of them was mooing! She couldn’t move but she kept the motor running: no way was she gonna stop and let them cows crush her and the car to death!

After absolutely ages a bloke appeared and even though the cows were still out there she wound her window down a little way and, and not sticking her head out but getting very close to the open bit, shouted: “OY! Wotcher fink yer doin’, wiv ruddy cows on the ruddy road?”

“This is a farming area, lady, we got a right to move our cows, it’s the law, see?” returned the man nastily.

“Then if yer got a right to move ’em, move the ruddy things before they squash my car!” she screamed, forthwith bursting into snorting sobs.

“No call to bawl, lady,” said the man uneasily, coming closer. “You can’t ’urry cows, see, it curdles the milk. They won’t squash your car.”

Joanna just sobbed, groping in her handbag for a hanky.

“Get up, you!” he said crossly to the nearest cow. There was a shout from somewhere in the distance and he shouted back: “Can you get ’em moving? This lady, she’s bawling!”

The voice in the distance shouted: “Come up, Blackie!” and a shrill whistle was heard.

“’E’s moving them,” said the cowman uncertainly to the sobbing form in the car.

Joanna just sobbed harder.

“Shit,” he muttered. “Get up, girl!” He patted a few rumps in the press, with not much visible result. “Oy, lady, they wont ’urt yer!” he cried.

No response. “Come on, get up,” he muttered. “HEY!” he shouted, edging away from the car and its sobbing occupant amongst the familiar warm flanks and bony hips. “What’s the ’old-up?”

More shrill whistling from the hinterland and the voice then shouted: “Bloody Blackie’s after rabbits! He’s turned the leader away from the fucking gate!”

“Well, ’ead her back!” he shouted, beginning to force a way through the press, muttering under his breath about not a cow dog and why’d he wanna bring the bloody animal in the first place.

The man had gone and the cows were pressing hard against the car. Joanna blew her nose hard but more tears kept running down her cheeks. It was stupid, but she couldn’t stop, and them cows was gonna crush the car, they was huge! Only if she tried to drive through them there’d be wounds and broken legs and blood all over the road!

“Get up!” shouted a voice. “Move along, old girls! Come on, get up! Shoo! Woo! Get up, then! –Are you all right, madam? The cows won’t hurt— Joanna!” he gasped.

Clutching her soaking hanky tightly, Joanna peered up at him blearily. “I might’ve known it was your ruddy cows!” she wailed, bursting into sobs all over again.

“They’re going. We were just moving them into the next field on the other side of the road,” said Allan lamely. “They wouldn’t have hurt you.”

“They was squa-hoh-hoshing us!” she wailed.

“Us?” he echoed uncertainly,

“Me and Pamela!” wailed Joanna, with a fresh burst of tears.

Dazedly he peered into the little car, but there was no-one else in it. “You haven’t let a dog out amongst our cows, have you?” he said uneasily.

“Eh? No,” said Joanna, blowing her nose hard.

Allan looked at the slim brown hands and the soaking dainty handkerchief and bit his lip. “That’d be one of the hankies that you scent with pot-pourri, would it?”

“No, ’s draw-liners,” said Joanna soggily.

His lips twitched. He came round to the other side of the car, giving the last couple of stragglers a friendly slap on the rump as he did so. “Open the door,” he said mildly.

Sniffing hard, she opened the door. Allan got in beside her. “Pot-pourri scented drawer liners, eh?”

“No, pot-pourri and cinnamon,” replied Joanna literally, attempting to blow her nose again.

“Have mine,” said Allan with a smile, handing her a flag-like thing.

Joanna blew her nose obediently.

“I think it probably smells of cows,” he admitted.

“Yes. They got a real pong.”

“It’s only grass being processed,” he said mildly.

“Yeah, s’pose it is, really.”

“If Pamela isn’t a dog, who is she?” he murmured.

“The car,” replied Joanna on a glum note. “Don’t laugh; I bet your cows ’ave scratched ’er!”

“I don’t think so,” replied Allan, his mouth twitching. “There aren’t many sharp bits on a Jersey cow.”

“That’s it! All I could fink of was jumper.”

Allan’s shoulder shook. “No, the cows aren’t jumpers.”

“Go on, laugh! All you ruddy Tarlingtons are the same!” she wailed, bursting into renewed sobs.

Allan simply put his arm round her shoulders and waited until the sobs died away.

“’Ere! Wotcher fink yer doink?” she gasped as he then fumbled at her hip.

“Sorry. Undoing the damned seatbelt. That’s better,” he said, getting his arm round her more firmly.

Joanna knew she ought to say something. Tell him where he got off or point out that after ignoring her for two whole years he had no right to—to—

“I apologise for being an up-myself shit and a—a ruddy Tarlington and a total prat, Joanna,” he said.

She ought to flatten him, only his voice had had a definite wobble in it. “Oh,” said Joanna faintly.

“I—I know I’ve no right to say this, but I haven’t stopped thinking about you for two years, Joanna! Can you forgive me?”

Joanna swallowed hard. “Um, ’tisn’t really a matter of forgiving. Um, I’m still me and you’re still you,” she said in a tiny voice. “And I dare say I won’t see hide nor ’air of Louella for a bit, until she wants somethink else out of me, but she’s still a relation.”

“Um, yes. Cynthia Moreton’s still my relation, too, I’m afraid, and just as bloody awful as she was at that social where we had those lovely dances.”

“Mm,” replied Joanna, chewing on her lip.

“Um, look, if you hadn’t come down I would have contacted you. Hill’s pointed out the error of my ways in no uncertain terms, but I— Well, that did encourage me,” said Allan glumly. “I suppose I’m the sort that does need a bit of a push.”

“You lost your nerve, didn’t you?” said Joanna slowly. “That day you came over and heard me shouting at Louella.”

“Yes,” he admitted, making a face.

“So what’s the guarantee you won’t lose it again?” she said grimly, sticking that lovely oval chin out but not looking at him.

“I—I suppose there are no guarantees in life,” replied Allan, his voice shaking again, “but I do know what I want, now. And, um, I don’t think I’d lose my nerve if—if we’d made it a permanent thing, Joanna.”

There was a short silence, during which Allan’s heart hammered painfully. He couldn’t see her expression, as she was staring fixedly into her lap. Then she said: “What about them ’orrible—those horrible society weddings and that sort of stuff that your lot go in for?”

“What, like that thing of Colin Haworth’s that Hill dragged poor Hattie to? I haven’t been to a society wedding since I was in my twenties, and I’d ask you if you wanted to go before accepting any invitations. And as a matter of fact I loathe bloody society does: far from dragging you, I’m more likely to expect you to be a stick-in-the mud stay-at-home like me. It’d be you dragging me, if anything!”

Her eyes narrowed. “Like, if Julian and Bruce got married, well, I mean, Bruce drives a lorry and Julian’s a hairdresser, wouldja come?”

“Of course, if you wanted me to. Actually I rather like weddings, so long as they don’t include the society lot,” said Allan with a smile in his voice.

Joanna gulped. “Yeah. Do ya? Um, no, I don’t think you’ve got it, Allan. It’d be, like, a gay wedding.”

“Yes, that’s what I thought,” he replied placidly.

“Oh. Good,” said Joanna lamely.

He was just about to ask her if she thought they might risk giving it another go, then, or words to that effect, when Bill Emery’s voice said loudly: “They’re all in, now, Allan, and don’t ask me to look for that bloody Blackie!” And Bill’s horrible hairy face peered in at them. “Is she all right? I told her the cows won’t hurt her.”

“Yes, she’s fine,” replied Allan tranquilly. “She’s a friend: I’ll see her safely up to the house. Don’t worry about Blackie, if he can’t find his way home by now it’s a pity about him.”

“But you can’t just leave ’im!” gasped Joanna in horror. “’E was yer pa’s dog, an’ all!”

Allan’s face was all smiles. “Yes, so he was, the blighter, which means he’s lived here bloody nearly as long as I have and knows every field like the back of his—well, paw! He’ll come home when he’s hungry, I can promise you.”

“Wouldn’t say that. When ’e wants food, yeah,” allowed Bill sourly. “Right you are, then. –Oy, hang on: Moira found that thing on the Internet about that new cheese you were interested in.”

“Oh, good,” said Allan, smiling at him: after all it wasn’t poor old Bill’s fault that he’d rather he was at Jericho. “Can you ask her to email it to me, then, Bill?”

“Well, I will, only does A2 milk stay A2 when you’ve added rennet from God knows what sort of other cow and turned it into cheese?” he responded darkly, mercifully stepping back.

“Go: quick!” hissed Allan, hurriedly buckling his seatbelt.

“Um, yes,” said Joanna dazedly, mechanically doing her seatbelt up. “A2: that’s it, I been trying to remember it for ages. Fort it was ABC or somefink.” With this she set “Pamela” in motion.

“ABC milk from Jumper cows, yes!” he choked, going into hysterics.

She glanced at him uneasily. “Hah, hah.”

“Sorry,” said Allan feebly, groping for his handkerchief and finding he no longer had it. “Every trade or profession has its own vocabulary, after all.”

“Um, yes. Um, what was that Hattie said? Oh, yeah: they need to have them, to validate themselves by.”

Allan gulped. “How too horribly true.”

“But what is it?” she asked, frowning over it.

Allan explained what A2 milk was, the explanation lasting until they were at the gate. Then he had to direct her up the drive, which she could see perfectly well for herself, and point out Ma’s blessed flah garden, which she could see perfectly well for herself. And then he had to become very busy opening doors and helping her out of the car and showing her into the house.

At which point they found themselves alone in the front hall.

“Um, everyone’s out, Ma’s taken the girls to the cinema in Brighton. Well, whole-day treat, really: drive over in the morning, lunch somewhere unspeakable of their choosing, then the cinema, and I’m expecting a phone call around five to say they’ve decided to eat something that passes for dinner over there.”

“I see,” said Joanna in a tiny voice.

“Um—come through.” He showed her into the sitting-room, where she sat down neatly on a flowery sofa and looked up at him expectantly.

Allan passed his hand through his hair. “Oh—God,” he said, suddenly collapsing onto a chair.

Joanna swallowed. “’S all right,” she said hoarsely. “You don’t have to say anything more.”

“I think I damn’ well should!” he said, looking up with tears in his eyes. “I—I don’t think you actually said, before. Can you forgive me?”

“Um, yes,” said Joanna in the thread of a voice.

Allan got up unsteadily. She was giving him that expectant look again, out of those huge dark eyes; he sank to his knee beside the sofa and buried his head in her lap.

Joanna looked down at his neat light brown hair, biting her lip. After what felt like a very long time she put her hand tentatively on his head. At this Allan put his arms right round her waist. Crumbs: she could feel him breathing, right in a very rude place. Unfortunately it wasn’t that exciting—well, it was, but not all that, because she shouldn’t have had that ruddy cup of coffee, she was dying to go to the toilet! She couldn’t remember what was the polite way to say it for people of his class, ’cos her and Hattie had compared what was polite, or U and non-U, Hattie had called it, in Britain and Australia, and then Hattie had gone on about American polite expressions for it as well, and now she was hopelessly mixed up!

“Um, sorry, but could I go to the toilet?” she said, far too loudly. Now he’d think she wasn’t a lady, help!

Allan sat back abruptly. “Yes, of course.”

“Sorry,” repeated Joanna lamely. “I shouldn’t of had that cup of coffee. Is it upstairs?”

He was about to say there was one downstairs, but thought very much better of it. “Mm, come on,” he said, scrambling up.

Joanna came with him obediently and allowed him to show her into his ensuite bathroom without apparently noticing anything odd about the procedure. Allan tottered over to the bed and sank onto it, his heart racing. He had a strong feeling that a chap like Hill at this stage would chuck his clothes on the floor, sort of reinforcing the point, as it were, only unfortunately he wasn’t that sort of chap.

As she came back in, looking very shy, he said huskily: “At this point a chap like Hilly would have all his clothes off, ready to leap on you, but I’m not that sort.”

“No. Good. He does rush into things, doesn’t he? I don’t think Hattie finds it very easy to deal with.”

“No. Um, well, as I say, we’re on our ownsome for the day, if you should feel like taking up where we left off?”

“Mm. Only, um, what about after?”

Allan scratched his head. “Uh—well, how about this? Ma rings up around five, as I said, I tell her you’re here and order her to get takeaways for the lot of us, and we all end up having a disgustingly unhealthy dinner of fish and chips or pizza or whatever the kids fancy.”

Suddenly Joanna’s eyes filled with tears: what a nit! Just when he was obviously expecting her to say something light and airy.

“Um, well?” said Allan weakly. “Sound all right?”

“Yes,” she managed. “It sounds like Paradise, actually.”

“Oh, Lor’, don’t cry again, darling!” cried Allan, forgetting his own nerves and rushing to hug her. “Don’t,” he said into her hair as she burst into tears on his shoulder.

“Sorry,” said Joanna at last. “It wasn’t very romantic. I mean, it was, only I then I had to go and spoil it. Just like me.”

“Eh?” he groped.

“Downstairs. Like when I hadda go. Is saying toilet polite?” she added glumly.

“Perfectly. –Oh! I see! Not very romantic! No, well, life tends not to be.” He looked at her cautiously. “Disappointed?”

“Me? No, ’course not!” said Joanna, sniffing hard. “I thought you were.”

“No. Kiss me— No, hang on, let me get you a clean handkerchief.” He released her and fetched one from his drawer. “Not smelling of cows,” he said, giving it to her.

“No. Ta,” agreed Joanna, sitting down on the edge of the bed. She blew her nose hard.

Since she was there, Allan came to sit beside her and put his arm round her shoulders. “Do you want to?”

“Yes, awfully,” she admitted, holding her face up.

“Oh, good,” said Allan weakly, kissing her. Then he really kissed her. Then he got his hand inside that fetching orange blouse with the silly gathering business down the front—not that puckers over the tits were bad, mind you, and they certainly encouraged a chap to look at them! They felt as glorious as he remembered them, and she smelled as wonderful as he remembered her. In fact so wonderful that he had to get his hand inside her slacks. Then he had to haul them off and breathe in a bit of that— At this point it all sort of went out of his control because she grabbed his head and shrieked: “Yes! Do it, Allan!” Putting her legs right up. So he hauled the panties off and shoved his face in there and Joanna shrieked: “I want to-oo! Oh, ALLAN!” And Allan, forgetting everything about being a little gentleman and X minutes of foreplay and, well, everything, tore his clothes off, fell on the beautiful brown length of her and shoved it up there. At which Joanna let out a shriek like a banshee, moved fiercely on him, and came like a whirlwind for him—not that he had much leisure to notice it, because he was coming like the space shuttle taking off.

About ten centuries later he rolled off her and, groggily drawing her head onto his shoulder, managed to say: “My God.”

“Mm!”

Some considerable time after that, Allan managed actually to articulate: “My God! And I thought that first time we did it was good!”

“Mm,” agreed Joanna, raising her head and smiling at him.

“Jesus, I thought you were going to take it off!” He managed to squirm onto his side with the last remnants of his strength and breathed into her perfect café au lait ear: “I think that’s what’s technically called a young, tight cunt.”

Joanna gulped.

Yes, well, that sort of proved it, if Hill’s trenchant reproof hadn’t already done so. He got his arms right round her and said: “It was miraculous, darling Joanna. I felt—well, can’t describe it, really! I felt as if you were drawing me into you and—and at the same time, um, well, completing me, and asking me to complete you.”

“Yes,” said Joanna smiling her serene smile at him. “That an’ all.”

An indefinable time later Allan sat up, blinking. “Oh, Lor’, did I drift off? I apologise unreservedly, darling! What a clod! After you came down all this way to see me, the least I could do is stay awake for you!”

“That’s okay,” replied Joanna, smiling at him. He was just about to snuggle down and point out that he felt quite revived, really—almost revivified—when she added: “But I didn’t come to see you.”

“Eh?”

“I came to see Hill. To tell him that Hattie’s really miserable and she didn’t mean to be wild with him or any of that stuff what she said, and ask him to come back. ’Cos she keeps crying.”

“Oh, good grief! You’ve missed him, darling! He’s gone back to her. Set off yesterday. Um, late afternoon? That’s right, Ma had decided to do that slow roast chicken thing, takes ages, though it’s worth waiting for, but it was after the milking, so it was quite late. I suppose the roads were very busy and he decided against arriving late at night. He was probably driving towards Abbot’s Halt as you were driving away from it.”

“Ooh ’eck, ’ow silly!” she gulped, clapping a hand to her mouth.

“Yes, isn’t it?” said Allan with a laugh. “Come here! Let’s try something even sillier!”

“Ooh, Alan! OOH!”

Quite. Allan got on with it. Actually it wasn’t as silly as all that.

It wasn’t until they were in the kitchen and he was ineptly preparing some sort of meal—it was well past lunchtime and not nearly dinnertime, but ham, tomatoes, a bit of leftover cold roast chicken and some cold roast spuds could hardly be classed as tea—that it dawned.

“Fuck!” he gasped, dropping the knife with which he’d been ineptly chopping the tomatoes.

“What?” said Joanna mildly, bending to retrieve it before he could move.

Allan’s face was very, very red. “I forgot to take precautions. Jesus, both times! I’m so sorry, sweetheart!”

“That’s okay. My period’s due in a couple of days,” she replied with her usual calm.

“Are—are you sure, darling? Don’t want to dash off to the doc for the morning-after pill?”

“No, it’s okay. I’d of stopped yer, otherwise.”

Would she? Could she have? Allan goggled at her. On the whole he rather thought she would and could. And it wasn’t at all a bad thought!

No comments:

Post a Comment