29

Conclusive Crises

“Eh?” said Hill dazedly next day—the twenty-seventh—as Colin informed him crisply he wasn’t ringing to wish him the compliments of the season.

“Haven’t you seen the news?”

“Uh—no, the telly’s been entirely occupied by Kenny’s set of Star Wars and Gordon’s rival something even worse— What?”

“There’s been a frightful tsunami off Indonesia. Huge sections of Thailand and Sri Lanka taken out as well as half the Indonesian coast.”

“Shit. That sounds bad.”

“Hill, it’s a global emergency!” said Colin loudly.

“Uh—oh. God, ’tisn’t the part of Thailand that your cousin Willi favours, is it?”

“She’s in Scotland sucking up to an old great-aunt she imagines is going to leave her the Georgian silver, but yes, it is that area. I don’t know anyone who’s over there, but that isn’t the point.”

Er—no…. What exactly was the point? Colin was supposed to be in the throes of managing his crafts enterprise. It wasn’t a busy time of year for them but the craftspersons were all beavering away making artefacts for next summer’s tourist season. And, just by the by, Penn was due to have their baby in something like six weeks’ time!

He was going on about the big international charity his brother-in-law was a fund-raiser for. Okay, Colin, they probably could do some good if they could get funds and supplies over there and okay, Colin, you probably do know some chap with a fleet of cargo planes—

“Colin!” said Hill loudly at this point. “Haven’t you got responsibilities at home?”

“They made not need me, but if they do I can’t not go. Penn’ll understand.”

Possibly she might, but that was not the point!

“Look, Colin, you aren’t foot-loose and fancy free; what if you’re off helping with disaster relief when Penn has her baby?” said Hill loudly. –Since he’d been sitting in the kitchen watching Hattie cook when the call had come through she was now gaping at him in horror. He made a face at her and nodded grimly.

“Of course I’ll try not to be. But it’ll come whether I’m there or not. Half the chaps in the regiment missed—”

“For God’s sake, man! They had no choice! You’re not in the Army now! The baby is yours as well!”

“Penn will understand,” he repeated. “This is the sort of thing that happens once in a millennium, Hill, you haven’t grasped the scope of the disaster. Put the telly on: you’ll see.”

“I don’t need to put the telly on to tell you’re out of your mind!” retorted Hill angrily. “Haven’t you ever heard of the phrase ‘charity begins at home’?”

“I think my counter to that one is ‘the greater good’. Turn the news on. You’ll grasp the scope of the disaster. I can put you in touch with several people who’d be glad of your organisational skills, once you’ve thought it over.”

“No. It’s taken me nigh on forty years, but I do now know what my priorities are,” replied Hill grimly. “Don’t ring me back until you come to your senses, thanks.” He hung up on him.

“Bloody Colin. Gone raving loony: thinks he’s gonna save the world single-handed. There’s been a huge tsunami off Indonesia. Apparently this means he has to desert Penn and his craftspeople and hive off and help with the relief effort,” he said grimly to Hattie. “Come on, we’ll put the telly on.”

They put the telly on. Okay, it was appalling and Colin was right: it was a once in a millennium thing.

Hill found that Hattie was looking at him fearfully. “No, darling,” he said firmly. “Whatever Colin may say, I am not rushing off leaving you and the boys to fling myself into relief work that five million other chaps could do as well as me—no, better.”

“Good,” said Hattie faintly. “Maybe we could give some money to Oxfam.”

Exactly. Like normal people, not maniacs like Colin Haworth! “Yes. We’ll do that, darling. Kenny, grab a pen and next time there’s some intel about Oxfam, write it down, would you?”

Looking relieved, Kenny rushed off to find a pen.

“It hadn’t dawned before,” admitted Hill grimly, “but Colin’s got a Helluva lot of his father in him.”

“Ugh, Holy Paul?” replied Hattie faintly.

“Uh-huh. A really big good cause beckons and immediately labelling it the call of duty he rushes off in pursuit of it, regardless of what commitments or responsibilities he might have at home or who he might hurt in the process. Colin once actually told me that the longest continuous space of time he or his brother and sister ever spent in their father’s company was when he was in his bloody pulpit of a Sunday.”

“So you aren’t gonna go with him if he does go off to Thailand or somewhere?” said Kenny hoarsely, coming back with a pen and a notepad.

“No, Kenny, I’m not,” said Hill grimly.

“Good. I mean, you’re right: lots of other people can do that,” he said awkwardly.

“Quite. Qualified people, what’s more. I’m not saying that Colin doesn’t have good organisational skills and very possibly he does know a rich chap with a fleet of cargo planes, but—” He drew a deep breath. “Forget him: he’s a maniac and frankly, always has been. Tell you what we can do, and that’s organise some collection tins in the village.”

“Yeah! I know! We can use those coffee tins she’s been saving!” Kenny rushed out.

“Saving coffee tins?” said Hill faintly to his beloved.

“Instant ones. The big ones. I worked out it was cheaper to buy it in bulk. They’re too good to throw away.”

“Good, they’ll be just the thing,” he said calmly. He got up as the phone in the passage shrilled. “That’ll be Ma E. with a rival collection scheme, so I’m telling you now”—Hattie was looking at him fearfully—“we’ll combine ’em!” said Hill with a grin, going out.

It was. She was very glad to hear they had a collection of coffee tins, because Miriam Green had only been able to produce a clear plastic jar with a screw-top lid and although it might encourage people, it wasn’t wholly desirable for “everyone”—she meant the sticky-fingered village kids—to see what was in it. Hill agreed smoothly that the guests at Chipping Abbas would of course wish to contribute, not pointing out that they were all in the income bracket that’d just write a huge tax-deductible cheque, and agreed that she would, could and should be the one to trot up there with a tin or two.

Kenny was about to operate on the coffee tins’ lids with a sharp instrument but he stopped him forcibly, and they all got into their anoraks and went round to the garage, where George Jukes, very relieved it was them and not Mrs E., was only too happy to make proper slits in the lids with the proper tools. And to accept a tin, noting happily that he was getting more custom these days with Chipping Abbas open at last! Then they went round to Miriam’s and transferred her takings into a proper tin. One pound and thirty-five P. Oh, of course: she’d only just reopened. The stout Mr Rushforth came in, well muffled up, just as Gordon was choosing the exact position for the tin and, looking relieved, stuffed a tenner in, with a muttered aside to Hill that of course he was sending a cheque to Oxfam as well, but one had to support the village effort, hey?

Exactly. Hill let Gordon put his own fifty P in and then gave him a tenner from him to stuff in as well. Gordon and Kenny then thought they could take a tin and go round door-knocking! Hill looked at their eager faces. “Oh, why the Hell not? And tell you what: I bet there’s no-one in Chipping Ditter that’s thought of that! Why don’t you do the village now, then we’ll have some lunch and then we’ll nip over to Chipping Ditter! –That okay with you, Hattie, darling?”

“Yes,” said Hattie. “That’s a great idea. There’ll be people that won’t be going out in this weather.”

“Right. Charity begins at home, eh?” said Hill, putting his arm round her.

“Yes,” she said swallowing hard. “Poor Penn. I know she’s a very capable person, but—but heck, Hill! Um, I suppose Colin won’t think better of it and stay home?”

“No,” said Hill grimly.

Hill was right, and Colin was in London within the week, doing some daft liaison job for the chap that owned the cargo planes that five million other chaps whose first baby wasn’t due could have done. Stupid ass.

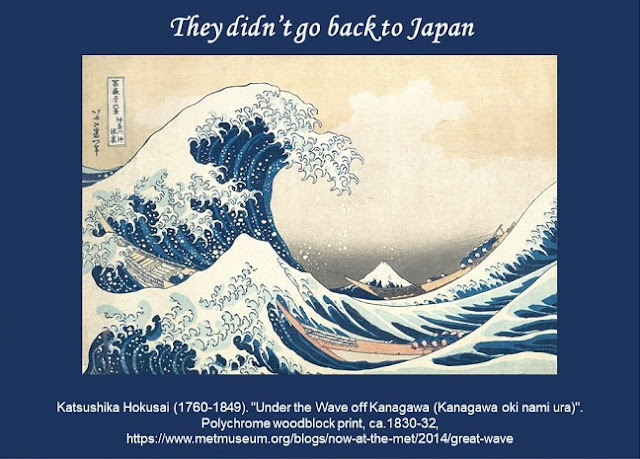

They didn’t go back to Japan. Whether it was the shock of the tsunami or Hattie’s relief at finding out that Hill really did intend to put her and their life together before anything else, or just the glaring example of bloody Colin’s idiocy, or even the fact that Hattie had missed him— Well, Hill honestly couldn’t have said. But whatever it was, nobody seemed keen, not even Ken—in fact he seemed very keen on getting a cottage put up on the vacant lot next-door as soon as possible and seeing as much of Ma as he could, appearing thrilled to accept an invitation to Guillyford for the New Year. Hattie rang Toshiro Watanabe and, presumably, apologised: it sounded grovelling. She didn’t contact the Polytech to ask if they might have any more tutoring for her, so Hill didn’t prompt her—he wouldn’t have minded, if that was what she wanted, but he was rather glad she seemed perfectly content to stay home most of the time, with just the odd bit of interpreting for the Mayor of Ditterminster or for YDI, so long as it wasn’t abroad.

Hill’s next conversion project was a rambling, broken-down manor in Lincolnshire, but as this was only in the preliminary planning stage most of his time was spent in the office in London. It wasn’t altogether a satisfactory arrangement, the more so as he was sticking grimly to Ma’s scheme and not actually living in the cottage, but at least it was a lot easier to see Hattie, and take her out for a meal or the cinema or even get her up to London and take her to the theatre, than it would have been if she’d been in Japan, still! One could draw a veil over the ’orrible evening at the panto with Gordon, Sean Biggs and Brad White, but that apart, these jaunts were extremely enjoyable. And gee, Ma was right, he and Hattie did get to know each other and Hattie seemed much, much more comfortable with him. And, he had to admit it, much happier.

“I think I’ll have to go this bloody Opening in New Zealand,” he admitted glumly. “Maurice jacked it up months back. Thought you’d still be in Japan, you see.”

“Yes. That’s okay,” replied Hattie mildly.

“Um, you couldn’t manage to come, could you? Kind of an extended dirty weekend together? We haven’t really had one of those,” said Hill meekly.

Hattie laughed. “Is it on your Ma’s timetable, though?”

Hill had finally told her the lot: it seemed sensible, and God knew he didn’t want to keep anything from her! To his relief she’d taken it really well. Well, by that time she’d got to know Ma, of course. “Hah, hah,” he said with a silly grin. “Well, uh, pretty much bound to be, if it’s the norm! Um, think Ken would wear looking after the boys for week?”

“Um, well, we’d better see what everyone thinks.”

Rather naturally Kenny and Gordon thought they should come too but even they didn’t float that one seriously and everyone seemed happy for Ken to look after them for a week, so they went.

That was, they all went to the airport, complete with the fucking Porcosaurus! It had spent the past two months sitting quietly on Gordon’s chest of drawers, apparently ignored.

“Gordon, you don’t need to bring that toy,” said Ken firmly as he approached the car with the dreaded object under his arm.

“I do! And ’e isn’t a toy, ’e’s a brontosaurus!”

“It’s all right, Ken, it can come,” said Hill heavily.

Awarding Ken a quick glare before the vindicated smirk took over, Gordon and Porcosaurus got into the back seat.

“It’s a Linus blanket, it’s finally dawned,” said Hill heavily.

“Um, yeah. Who told you that?” asked Hattie numbly.

“No-one, darling: I’ve been reading up. See, I am taking you as seriously as my bloody projects!”

“Yes,” she said, very pink and flustered. “Are you? Um, good.”

“I thought the buh-rontosaurus was relatively new,” said Ken feebly.

“It is, Ken,” said Hill, smiling at him. “But evidently one doesn’t have to have had the thing from one’s earliest childhood for it to play the rôle! One of the misguided girls from the upstairs flat bought it for him after the fire—at a foul airport boutique, I think.”

“Ah, yes. One of the air hostesses,” he said calmly. “I see. Then I shan’t try to wean him off it. –Hop in, Hattie, we don’t wanna be late!”

That last was pure Australian! Hill helped Hattie into the car, smiling.

February. New Zealand. Hattie collapsed in helpless sniggers, gasping: “Bottles!”

“Yeah,” said Hill, grinning widely. “Well, this is it, darling. If it isn’t as comfortable inside as Jim’s sworn we’ll sack him and Throgmorton.”

“Hah, hah,” said Jim Thompson calmly. “It is, Hattie, you’ll see. If it’s too hot you can put the air conditioning on: I’ll show you.” –It was very warm. Several people had mentioned to Hill that February was usually the hottest month, out here. This would explain why the New Zealand schools went back after the Christmas break around the first of Feb, then, would it?

They went in. Hattie gaped at the objects sitting around on the beautiful recycled-wood floor of the sitting-room. All the cushions were covered in creamy canvas—very eco-friendly, creamy canvas was, Hill had seen it on several rival establishments’ websites—but although this was a unifying factor, the furniture was a very odd mixture indeed. Those pieces that had visible wood had had been stripped and oiled or waxed within an inch of their lives, so this could have been said to be another unifying factor—

“Recycled—recycled—recycled—that’s new, but the wood’s recycled,” said Jim, pointing. “Sir Maurice was really keen on the snap of a driftwood coffee table with a recycled glass top the designer sent us, so—”

Hill collapsed in helpless sniggers, gasping: “Don’t go on!”

Grinning, Jim said to Hattie: “I’ll show you the bedrooms. Don’t ask how inner-sprung can pass as organic and eco-friendly, will ya?”

Hill wiped his eyes and waited. There came a whoop and a shriek of: “More bottles!” Then she collapsed in helpless giggles.

Exactly. Hill went into one of the two palatial bedrooms of Fern Gully Ecolodge’s eco-friendly bottle cabin, grinning.

She did admit later, leaning on the bedroom’s tiny balcony and gazing at the view of a deep blue lake under a clear blue sky, that it was a glorious setting. Hill agreed—but that only made it better, really, didn’t it?

Fern Gully Ecolodge was fully booked for the week after the Opening, so Hill and Hattie removed thankfully, bag and baggage, to Taupo Shores Ecolodge and nice Jan Harper’s cooking.

“Real food,” said Hattie with a deep sigh, tasting the cold oven-baked lemon chicken Jan often served for summer lunch.

“Yeff,” agreed Hill through a mouthful of Jan’s miraculous real potato salad.

Hattie chewed and swallowed. “How do people that stay at fancy hotels stand having little fancy piles of stuff served to them for every meal?”

“Don’t ask me,” replied YDI’s Senior Project Manager simply.

The phone call from Hampshire came through around ten in the morning when they were sitting on the ecolodge’s landing stage debating in a desultory manner whether to go for a stroll down one of the trails, or just do a bit more sitting and dabbling of the toes in the water. Or as a special treat go along the shore to one of the tiny beaches ringing the big lake and throw pumice stones into the water. The beaches were covered with ’em and they floated! Something you couldn’t describe, you had to experience it!

Jan arrived at the landing stage panting, mobile phone in hand. “You don’t really know that actress, Lily Rose Rayne, do you?” she panted.

Hill blinked. “Well, yes. Sort of. In private life. She’s married to a friend’s cousin.”

“’S for you, then!” she panted, holding the phone out.

Hill took it in a palsied hand. What the—? “Hill Tarlington.”

“Is that Major Tarlington?” cooed a completely strange female voice. He admitted it was. What the—? “Hold the line, please, I have a call for you from Miss Lily Rose Rayne.”

Hill held the line.

“Are you there, Hill?” said a familiar Australian voice.

“Hullo, Rosie, so it is you,” he said limply.

“Yes. I hadda pull the Lily Rose Rayne crap to get them to make the toll call: it’s a private clinic, Colin chose it. ’S all right, it’s good news: Penn’s had her baby, a boy! Mother and baby doing very well!”

Hill’s knees went all saggy. “That is good news, Rosie! Uh—dare I ask if the silly clot managed to be there, rather than in Brussels or Strasbourg or bloody Geneva?”

“Yes, for a wonder,” replied Rosie on a grim note. “He’s taking two weeks’ paternity leave, too, believe it or not. Is Hattie there?”

“Oh, Hell, yes!” said Hill with a laugh. “Give her all the details, Rosie, by all means!” He passed her the phone, grinning. “Penn’s had her baby. Rosie’ll fill you in.”

They yacked for ages. Hill looked at Hattie’s very pink cheeks and shining eyes and didn’t say a thing, not even that they were tying up the ecolodge’s phone.

March. Bloody Western Australia. A glorious week of freedom with Hattie had meant, apparently, that he had to undergo two weeks of Purgatory looking at swingeingly hot and humid sites in the Cook Islands, swingeingly hot, humid and to boot crocodile-infested sites in northern Australia, and very dull sites in Western Australia, which he in his blindness had thought might be interesting: full of red dust, and giant trees and—and giant mines, at the very least! Or pearl fisheries: didn’t they have—? Not in these parts, no. That was all thousands of miles further north or further inland or, at any rate, not here. There weren’t any wildflowers, either. It was all farm land, or possibly, taking a second look at it, farmed-out land—degraded to the point of useless. Over in that direction there were reputed to be wineries but unfortunately you couldn’t see ’em from here or, in fact, without a four hours’ drive. And Jim could shut up about the speed limit! Jim pointed out that it hadn’t been his idea, it was a mate of Sir Maurice’s, but then did shut up. There manifestly was nothing more to say.

The phone call from Hampshire came through around nine in the morning when Hill and Jim were sitting in their very dull motel unit with its view of degraded fields and a slice of highway, debating in a desultory manner whether to give it all away or look at one last site, even further south, which Jim thought might be nice, or at least not as bad. Um, yes, it was all farming land down there, Hill. Um, nowhere near the Nullarbor, no. Um, Europeanised? Well, yeah, probably.

“It’s John Haworth here. It’s bad news, I’m afraid, Hill.”

Colin had died quietly in his sleep that morning. No, thank God, it wasn’t Penn who found him, she’d gone down to her smithy. He’d been working very hard up in London, commuting every day and getting back very late. That clot on the brain the bloody neurosurgeon hadn’t been able to get at, the doc thought.

Hill didn’t point out that John’s last word on that subject had been to the effect that the clot had dissipated, because shit, what was the point? He thanked him for letting him know, said he didn’t know if he could make it back for the funeral, and hung up.

Jim hadn’t gone away: he’d taken one look at Hill’s face and stayed on the spot. “Who’s died?” he said tightly.

“Colin. Uh—sorry, Jim, he’s—”

“I remember,” he said calmly. “The one that was shot up in Iraq that time we were at Big Rock Bay. Hasn’t his wife just had a baby?”

“Yeah.” Hill passed his hand over his face. “Apparently it was a blood clot on the brain. I was under the impression his scans showed he was clear, but—”

Jim got up. “I’ll get you a drink. Then we’d better see about getting you home, pronto.”

“Uh—Jim, he wasn’t a relative, I dunno that YDI’ll wear—”

“They can get fucking choked,” replied Jim militantly, marching over to the fridge.

On second thoughts, Hill did so agree with him!

Theoretically one could travel from Western Australia to London in less than twenty-four hours. That was the theory. In practice there was the fact that they were around four hundred and fifty miles from the nearest international airport. Then the bloody hire car broke down. Quite a few cars shot by them without stopping to see if they were in trouble—quite a few. So much for Aussie mateship. They were finally towed into a small town where the garage owner thought it would be much easier to fix ’er here, rather than phone for a replacement, mate: see, it’d have to come from the nearest office— Yeah, yeah. They phoned anyway but the answer was a lemon. No, mate, there wasn’t a taxi, not round here! Well, ya could get the bus but that only came through— Whenever, they’d missed it. It was gonna take twenty-four hours whatever they did.

They shared the driving but even so it was over thirty hours before they finally limped into Perth. They’d missed the first two flights Jim had provisionally booked Hill on. Well, the second two, they’d long since missed the first one. They could try going straight to the airport, might grab the next, but Jim sort of thought that with all the new safety precautions at check-in— Jim was right. Theoretically there was still over an hour before the plane was due to take off by the time they got there but there was no way Hill was gonna get on it.

He dozed on a plastic chair while Jim rushed round finding an alternative. Gee, the ones that usually went through Colombo had been rerouted because of the tsunami, fancy that. Okay, he’d go straight to wherever. Johannesburg? So be it.

In Johannesburg they were all off-loaded because an engine had overheated. No-one had the sense to load them onto another plane: they were dumped into buses and carted off to a hotel while a replacement engine, or possibly whole plane, the message was extremely unclear, was flown out from London.

The plane did not go straight to Heathrow, though the ticketing person had sworn to Jim it was a direct flight. It went to various places, none of which would particularly have mattered except that one of them was Madrid and they landed in time for a bomb threat. No-one had the sense to load them onto another plane: they were dumped in a transit lounge and had to sit it out. Possibly better than being bailed up in the actual plane out on the tarmac, yes, but by this time Hill was past caring.

The fucking thing did eventually get him to Heathrow, where he fell into a taxi and, being completely jet-lagged by this time, just told it to take him to the flat. The funeral had either been today or it was tomorrow and his brain wasn’t capable of working it out.

He had meant to make a couple of calls before he passed out but when he woke up around nineish realised he hadn't. He rang Hattie at the cottage but there was no reply. He still wasn’t sure what day it was but managed to get Hellen at the office. Okay, the funeral was today. Uh—have Sir Maurice’s Ben Simpson and the Roller? Okay, if she said so. He managed to shower, shave and choke down a couple of water crackers and a cup of black coffee by the time Ben arrived.

If Hill’s latest intel from John was correct—which it might well not be, he’d spoken to him on a very bad connection from Perth airport—there was to be a memorial service in Bellingford for all friends and sympathisers, then the cremation in Portsmouth, close friends and family only, and then the wake back in Bellingford, apparently with the entire village present. The memorial was to start at ten. Ben didn’t think he could get him there in time for it—no, well, the man wasn’t actually a miracle worker, and if he, Hill, had the sense he was born with he’d have set the bloody alarm before he passed out—but he’d be in time for the cremation. Hill wasn’t too sure he was invited to that, but bugger it, he’d go.

“Good, you got here,” said John, wringing his hand excruciatingly hard.

“Just. Sorry I couldn’t make it to the first thing.”

“That’s okay, most of the family, half the regiment and most of the village turned out for it, invited not. They’re setting up for the wake and Terence has opened up the pub, that’s where most of them are. I’ve told the chap here to keep it bloody short and simple: Penn doesn’t need a bloody fuss.”

“No. Good. Who are the two chaps with her?”

“Her father, and the taller, craggy chap’s her mature-age apprentice at the smithy. Very good fellow.” He led him over to them, and Hill pecked Penn’s cheek and managed to say: “Sorry, Penn. Anything I can do.”

John then left him in Rosie’s care. She was red-eyed, but otherwise as lovely as ever: it was a strange feeling, really; somehow Hill felt she should have… deteriorated?

“John knew the blood clot hadn’t dissipated. He let it out to me not long ago,” she admitted as they drove back to Bellingford in John’s old Jag. “I don’t know why, but I sort of wasn’t surprised. Colin didn’t know. Um, there are some idiots, mainly his relations, that’ll try to tell you that’s why he insisted on starting the crafts project or why he insisted on doing the tsunami relief—or both—but ignore them, Hill.”

“Uh—ya mean they’ll try to claim his brain was affected?” said Hill dazedly. “Colin? Come off it! He was always a maniac!”

“Yes,” she said, patting his knee.

“Exactly,” said John from the driver’s seat.

“Absolutely, Hill!” agreed Rosie’s gay actor friend, Rupy, from the front passenger’s seat. “Definitely a maniac, but adorable with it!”

It wasn’t a bad epitaph, when you thought about it. And Colin would most certainly have appreciated it!

The Workingmen’s Club was glowing with bunting—even more so than for the wedding, really. Jesus, that was Rowena Sanderson, in a huge black hat—no, make that ’uge black ’at, in Colin’s memory! Hill accepted a brimming tumbler from a high-coloured, dark-haired chap who did seem vaguely familiar. Uh—fried oysters?

“Jack Powell,” the chap reminded him. “Get it down yer.”

Right. Hill got it down him. Crumbs, Willi Duff-Ross had turned up! ’Uge black ’at—right. Jesus, wasn’t that one of Colin’s German dames? Not the one that had been ousted by a general’s daughter, another one. Earlier. ’Uge black ’at.

“German dame,” said a familiar voice in his ear at this point.

“Hullo, Terence,” said Hill with relief to John’s brother. “Fucking bad show; what can you say?”

“Exactly. Get this down you, old man.”

Hadn’t he just—Oh, well. Hill got it down him.

“’Nother German dame over there, see? Plumper,” said Terence in his ear.

“Right: ’nother ’uge black ’at.”

“Exactly, old boy. Some of your pals are here,” he said, looking vaguely round at the huge scrum. “Uh—Jerry Coleby, I think. Loads of the chaps, the ones that aren’t still out there.”

“Uh-huh, seen some of them.”

“Can’t see Hattie,” said Terence, peering.

“Uh, no, she’s not with me, old man.”

“Eh? No, but she’s here.”

What? Hill peered frantically, wondering just how sloshed Terence was. Uh—no, by God! There she was! Ugh, being gushed at by a middle-aged dame in a ’uge black ’at.

“Who’s that with her?” he asked cautiously. “A relation?”

“Uh—No. Local identity. Gusher, mind you. One of Colin’s biggest fans,” he warned.

“I can take that, so long is it’s not a Duff-Ross or, forgive me, one of the hags on your side.”

“I’m with you,” agreed Terence. “Sanckermon’ous ’ypocrites to a hag.” Right, he was sloshed, but Hill didn’t imagine the sentiment was due to that.

He fought his way through the scrum to Hattie’s side. “Hullo,” he said meekly.

“Hill! You got here! We couldn’t get any sense out of the airline so I thought I’d better just come.”

“Good show,” he said, taking her elbow very firmly indeed. “Who brought you, darling?”

“Nobody,” said Hattie in surprise. “I came by myself.”

But she couldn't drive! He gaped at her.

“It was easy: I got the train to London, and then I got the train to Portsmouth, and then I got a taxi. I had plenty of money with me, I used my credit card,” she assured him.

Uh—last time she’d tried to use her credit card in his company she’d got the PIN number wrong. “Well done, darling.” He might have said something else, like he was very, very glad to see her, but gee, the gusher, who’d visibly been barely containing herself, broke into speech.

“So glad you got here, Major Tarlington! We did meet, at the wedding!”—Couldn’t remember her from Adam. Though, talking of which, he did vaguely remember Adam Gilfillan being there: was it him or Jerry that had looked down Hattie’s front? Both, probably.—“Shockingly ironic, isn’t it?”—Was it?—“So dreadful for poor dear Penn—with the new baby, too! One must just be very, very thankful that he lived to see it, poor dear Colin.” Well, she was genuine enough: there were tears in her eyes, so Hill didn’t say and also thankful the bugger had managed to turn up for the actual birth, he just nodded and agreed nicely.

“There’s hundreds of those ladies here,” warned Hattie as she finally gushed herself away.

“Noticed that,” he admitted. “All in ’uge black ’ats, too. About a quarter of them’ll be genuinely upset, like her; the rest are his bloody relations on both sides of the family. Don’t ask why they’ve come if they don’t care: they’ve come for pretty much the same reasons that most of ’em turned up for the wedding.”

“That’s a bit mean. Don’t you think some of them loved him, in their way?”

Hill had just caught sight of Lady Duff-Ross, Colin’s Aunt Louise, looking down her nose. He winced. “Some, yes.” He released her elbow in order to put his arm very tightly round her waist. “Thank you for coming, darling. Nice of you to bother to represent the horrible Tarlingtons.”

Hattie looked up at him in astonishment. “I didn’t come because of that, you nong!”

“Well, uh— Well, uh, of course you had met Penn,” he floundered.

“Not that. I don’t think she’s taken in who’s here or who isn’t, and I’m sure it wouldn’t matter to her if she had, poor thing. I came because I thought you might need me.”

Hill’s eyes filled with tears. “Mm. I do need you, very much. Thank you, Hattie.”

They ended up spending the night at Terence’s pub and, since Ben had long since gone back to Sir Maurice, letting Terence drive them to the station and slowly taking trains home. No doubt Ken would have collected them from Ditterminster station but Hill didn’t suggest it. They grabbed a taxi.

“Stay at the cottage,” said Hattie as they sped past ugly acres of rape fields.

“Lovely. Thanks,” replied Hill with a sigh.

“Um, no, I don’t mean just tonight,” she said, going very red but looking at him earnestly. “Move back in, if—if you’d like to.”

“Like to!”

“Your flat at Chipping Abbas is miles more comfortable, though,” she murmured. “’Specially the bed.”

“Mm. Uh, could swap them?”

“That’d be really nice. I’m sorry that I—I didn’t realise that I ought to change some things, Hill.”

“My fault,” he said, squeezing her hand very hard. “Bull at a gate.”

“No: it was my fault, too. But I—I’ve got used to the idea and I—I’ve missed you awfully, Hill,” said Hattie with tears in her eyes. “Colin wasn’t that much older than you. It makes you count your blessings.”

It sure did. Hill squeezed her hand again. “Yes. I’ll move my stuff back in tomorrow, if that’s okay?”

“Yes, lovely,” said Hattie with a deep sigh.

They were through the trendified horrors of Chipping Ditter and on the last stretch to Abbot’s Halt when she said: “Um, Hill, there’s something I ought to warn you about.”

“Mm?”

Hattie licked her lips. “It’s Gordon.”

Gordon had seemed pretty struck by Colin. “Reacted badly, has he?” asked Hill cautiously.

“Not—not exactly. Um, not in the way I think you mean.”

Hill’s admittedly limited experience of kids had now taught him that they didn’t by any means always react in the way one expected—and some of his reading had confirmed it. So he said mildly: “What? Being naughty? Nicking stuff?”

“No. Um, he’s held a funeral,” said Hattie, swallowing.

“Uh—shit, not one of the cats on top of everything else?”

“No, thank God. No, um, Porcosaurus,” she croaked.

“What?”

“Yes. He—he asked me about funerals and everything and—and then he produced Porcosaurus and announced it was dead and—and he was gonna bury it.”

Better than cremating it: the thing’d probably produce toxic fumes. “And?”

“Um, well, he has, Hill. He’s buried it in the veggie patch. Um, where I put those curly endive seeds in for you. Most of the ground’s pretty hard, you see, we’ve had quite a few frosts.”

Hill gulped.

“You—you won’t dig it up, will you?” she said anxiously.

“Hell, no! If the kid feels it’s some sort of closure— Hell, no! Let it stay buried. It’s better forgotten!” He hesitated, and then said: “Um, let it all stay buried, eh, Hattie? The—the past.”

“Me being stupid over the Henrietta Tarlington shit, ya mean,” she said glumly.

“Well, that’s part of it. Me being a bull at a gate, and all the skinny lady execs in my life, and— Well! All of it. Anything I may have said when I lost my rag with you. The lot.”

“Yeah,” said Hattie with a deep sigh. “That’d be good, Hill.”

Hill didn’t chance his luck by uttering another syllable: he just held her hand, all the way home.

THE END

of the story of “The Project Manager”

But the story of the New Zealand ecolodges continues

No comments:

Post a Comment